In my travels along Highway 11 I’ve noticed that some towns are:

In my travels along Highway 11 I’ve noticed that some towns are:

- really quaint (Earlton)

- super tidy (Mattice)

- a little goofy (Nipigon)

- kinda spunky (Moonbeam)

- surprisingly big (Thunder Bay)

- surprisingly non-existent (Lowther)

- seemingly on the edge of the world (Hearst)

And then there are some that are just plain cool.

Enter Cobalt.

Cobalt is just really neat. Part of it is the history. Part of it is the town’s independent streak. But mostly, it’s just so old and, well, old, that it’s really interesting.

From “Yikes” to “Cool”

My first impression of Cobalt was “oh god.” And not in a good way. But boy was I wrong. Cobalt is the kind of town that would have five taverns but no grocery store. And that’s what makes it so interesting.

It was when I stopped to take a break from driving that I really saw my surroundings. I realized that what looked old and run down was simply historic. That was looked grotty and old really had a tonne of character. That instead of tearing down older buildings and erecting cheap, shoddy new ones in their place, Cobalt had preserved its history. A history they were proud of. This place wasn’t run down, it was preserved. Cobalt was named Ontario’s most historic town for a reason.

Sure, there aren’t a tonne of stores or boutiques. But at least there aren’t a tonne of places selling crap either. There is no grocery store left in town (it closed in 1992 when the store owner cleared out the remaining products and held dance parties in the store to commemorate its closing), but what else is there is because it needs to be there – like museums, mine shafts, and bars. More than a few of them.

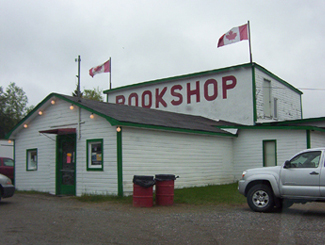

The Highway Book Shop was a classic tourist destination that never feels like a tourist destination. It was a family-run used bookshop on Highway 11 just outside of Cobalt and it is not only worth a visit, it is worth some time. Maps, books, magazines, teaching materials, kid’s lit, old books, new books, big books, rare books – you wouldn’t have believed all the crap they have in there. I think I spent an hour on two separate occasions perusing the cramped store. It might smell like your grandmother’s basement, but it’s really neat, and no visit to Temiskaming is complete without a stop, in my opinion. Sadly, the icon has closed. Ready to retire for years, the owners couldn’t find anyone to take the store on and had to shut one of Highway 11’s best attractions down.

The Highway Book Shop was a classic tourist destination that never feels like a tourist destination. It was a family-run used bookshop on Highway 11 just outside of Cobalt and it is not only worth a visit, it is worth some time. Maps, books, magazines, teaching materials, kid’s lit, old books, new books, big books, rare books – you wouldn’t have believed all the crap they have in there. I think I spent an hour on two separate occasions perusing the cramped store. It might smell like your grandmother’s basement, but it’s really neat, and no visit to Temiskaming is complete without a stop, in my opinion. Sadly, the icon has closed. Ready to retire for years, the owners couldn’t find anyone to take the store on and had to shut one of Highway 11’s best attractions down.

Cobalt Classic Theatre is the only remaining theatre from Cobalt’s heyday in 1920s. While other towns were using economic development funds to build golf courses, Cobalt restored the old Classic Theatre in 1993 and now hosts students, playwrights, and actors from across Ontario. The theatre is restored to what it looked like in the 1920s and is a focal point for the community.

Antique mining equipment on display at the lakefront. Other towns would have just thrown this stuff out. Cobalt, refreshingly, doesn’t run from its roots.

This headframe is now the world’s only bar in a mine headframe! That’s revitalization, northern Ontario style.

The Cobalt Mining Museum has the world’s largest display of silver and offers the only underground mine tour that I’ve seen outside of Timmins. The Bunker Military Museum has a good collection of memorabilia, the Great Canadian Mine show displays mining technology, and there is also a firefighter museum in town.

Cobalt also has two separate self-guided walks. The Cobalt Walking Tour brings you through town past historic buildings and historical places, while the Heritage Silver Trail is a self guided tour of many of the abandoned mine headframes in the area.

There’s more. There is Fred’s Northern Picnic, an annual music festival that the local Member of Parliament usually plays at (he’s a musician by trade) and where you get three days of music and free camping for like $60. The Silver Street Cafe has good food and decent prices, and they also cater local events with real food (forget hamburgers and hot dogs, think steak on a bun and pulled pork with onions.) The Silverland Inn and Motel is a restored hotel from Cobalt’s mining heyday and also serves food. There is a stained glass shop, a gem shop, and Iddy Biddy Petting Farm. Cobalt also has more murals than Nipigon.

Not sure if they’re still running Fred’s Northern Picnic, but that’s where I saw Serena Ryder before she was big, and the local MP get up and do a set too

Hockey, Streetcars, and Casa Loma

Hockey, Streetcars, and Casa Loma

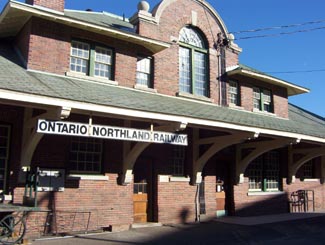

I read in the James Bay tourist brochure that there is a legend that Cobalt blacksmith Fred Larose threw his hammer at a fox, uncovering a rich vein of silver in the process. Further silver and mineral deposits were found in 1903, triggering a mining rush like no other in northern Ontario. The significance of the Cobalt finds supposedly led to riots over mining stocks in New York City. Others say that Cobalt built Bay Street (Toronto’s Wall Street.) A testament to the town’s wealth, the Cobalt Silver Kings played the 1909 season in the NHA, the NHL’s precursor. Another first in Cobalt include the Temiskaming Streetcar Line, which was installed between Cobalt and Haileybury, and was the first streetcar system north of Toronto.

In addition, the mines of Cobalt built Casa Loma, the famous “castle” built upon Spadina Heights in Toronto. Sir Henry Mill Pellatt was a wealthy Canadian mine owner (some say Canada’s richest man at the time.) It was his mining operations in Cobalt that allowed him to gather the immense wealth to build Casa Loma. Construction began in 1911 and took more than three years, 3.5$ million, and more than 300 full-time workers. With 98 rooms, it was the largest residence in Canada at the time. Pellat eventually lost his residence, as the Depression and the decline of mining in Cobalt led to his financial ruin. Casa Loma was essentially built with the revenues Sir Henry Mill Pellatt gained by draining Cobalt Lake for silver mining.

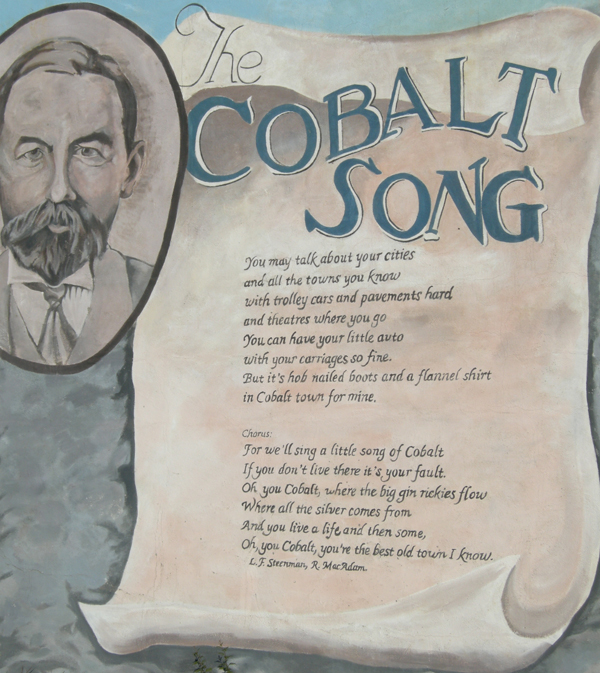

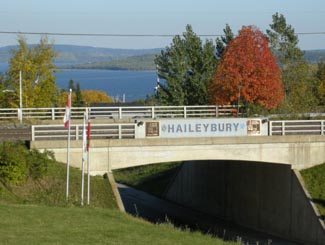

The Cobalt rush eventually produced more than $260 million worth of silver, countless myths and stories about how and where silver was found, who struck it rich, and who lost their pants in speculation. The Cobalt silver rush resulted in a whole little Cobalt culture developing – embodied by the Cobalt Song (click here to download the sheet music.) Cobalt led to the founding towns like North Cobalt (a bedroom town for miners) and Haileybury (a bedroom town for wealthy mine owners.) The mining boom in Cobalt also paved the way for exploration further north, which led to massive gold finds in Timmins and Kirkland Lake, both of which far exceeded the value of the mines of Cobalt in the long-run.

I could move this photo of downtown Cobalt closer to the text that talks about downtown Cobalt but in wordpress moving photos around is a pain in the rear. (Credit: User P199 at Wiki Commons.)

Although Cobalt survived the usual northern Ontario disasters, including a typhoid outbreak in 1909, and Great Fire of 1922, it couldn’t survive the decline of mining. Well, it survived, but it’s much smaller today and mining no longer exists. There is some exploration for diamonds, but I don’t think they’ve been found. I’ve heard that many of the old mines still have minerals in them, but that it’s just not economical to mine such old shafts for minerals at today’s prices. But, in the end, the history of Cobalt is one of a town that conbtinually gets kicked, but then manages to find its way back up.

Cobalt is considered the third part of the Tri Towns along with New Liskeard and Haileybury. But for some reason it didn’t amalgamate into Temiskaming Shores in the late 1990s when the province forced municipalities to squish together. Maybe it’s too far away. Maybe old hostilities with North Cobalt scuppered a move. Maybe the town is too independent. Maybe there is still an old hockey rivalry between Cobalt and Haileybury from the one season both towns had a team in the NHA. I’m sure someone in the town of 1200 put up a fight. I don’t know.

I haven’t spent as much time as I would like in Cobalt, and, I must admit, haven’t visited any of the touristy things here other than the Highway Book Shop. But I’m sure I’ll be back again.